John Reynolds: About the Author

Principal Consultant, Intertek

John Reynolds is a Principal Consultant with Intertek Asset Integrity Management, Inc. Before this, he was a Master Engineering Consultant with Shell Oil's Westhollow Technology Center in Houston. John joined Shell in 1968. Over the 38 years with Shell, he held various engineering and management positions in the United States and the Netherlands within the refining and chemical manufacturing fields, where he has primarily focused on mechanical integrity issues. John has served as master editor for several API Standards on FEMI and actively participated in the API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Subcommittee (SCIMI) and the ASME Post-Construction Committee. John is the past Chairman of the API SCIMI, the API Task Group on Inspection Codes, the API Task Group on NDE Technology, the API Task Group on API 580 RBI, and the API User Group on Risk-Based Inspection. John was also one of the foundational members of the API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Summit and gave the keynote address to the Summit in 2020.

Is this you? Please help us keep this page up-to-date by occasionally submitting your updated information.

Published Articles

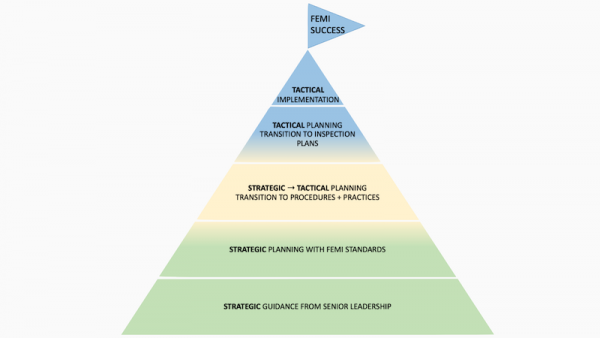

Both strategic and tactical thinking are needed within the FEMI work process, and we’ll show how important each aspect of the program is relative to the whole.

Navigating "shall" and "should" statements in regulations, FEMI standards, and internal company guidelines—what they mean and how to respond.

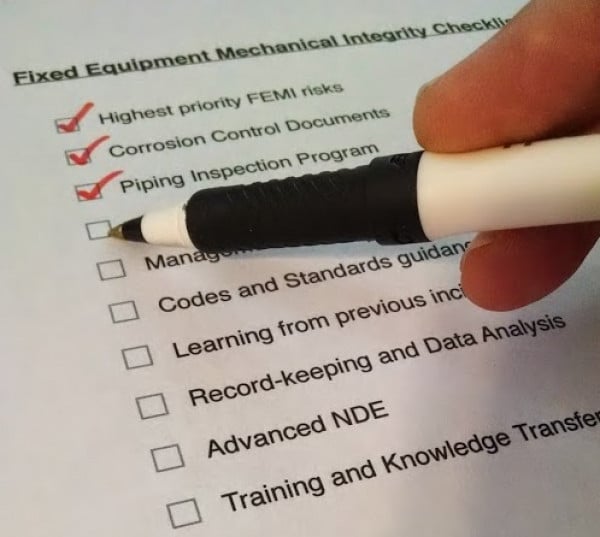

This article summarizes, at a high level, what the sites have been able to accomplish by implementing what the author believes are FEMI's best practices.

A look at the three types of fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) decision-makers you can encounter, along with the differences in the effectiveness of each.

A review of the plan one site put in place to upgrade their performance from the fourth quartile to the first quartile and keep it there.

This course addresses the top ten opportunities for improvement in fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) programs as identified by John Reynolds.

One of the most important aspects of FEMI management is to extend “stewardship” of assets beyond the work boundaries of those charged with fixed equipment.

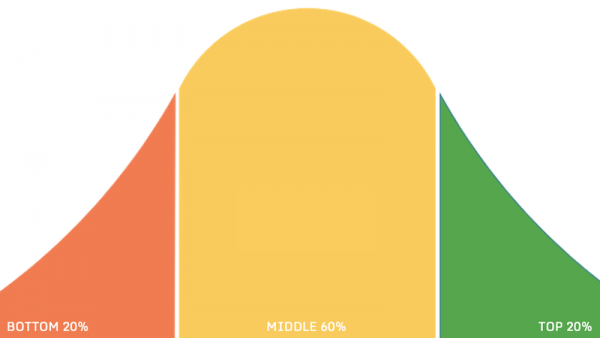

Are you an Inspectioneer? Are you a high-performing Inspectioneer? See where you fit on the performance bell curve and compare the different attributes that comprise a high performer with how you carry out your duties.

Do you know how a Good Engineering Practice (GEP) becomes a RAGAGEP? RAGAGEP clearly applies to all kinds of equipment, but this article will address RAGAGEP for FEMI used in the hydrocarbon and chemical process industries.

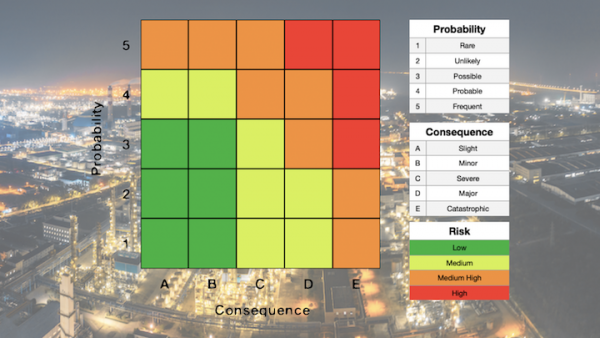

It is important to seek the optimum FEMI risk tolerance and understand how to manage risks by optimizing your risk mitigation strategies. Locating the FEMI "sweet spot" on the risk curve will achieve the best return on our FEMI investments.

Of the nearly 70 damage mechanisms listed in the latest edition of API RP 571, the highest FEMI risk may be the ones that are highly localized in nature and, therefore, the hardest to find.

There are a lot of potential threats that can interfere with maintaining adequate FEMI. Using situational awareness effectively to anticipate FEMI threats, understand them, and prepare the necessary steps can avoid a potential LOPC from the threat.

There is a major difference between fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) and fixed equipment reliability (FER). It’s important to differentiate between the purpose and reasons for the two programs even when they are often mixed together.

Utilizing a risk assessment methodology to determine the amount of detail in our QA/QC plans, as well as who needs to be involved, may help us improve both the effectiveness and the efficiency of our QA/QC work process.

This article discusses making continuous improvements in your fixed equipment mechanical integrity work process using the Plan-Execute-Review-Improve (PERI) model.

This article discussed the growing list of API FEMI standards, how some of them came to be, and why they keep getting improved upon with new lessons learned.

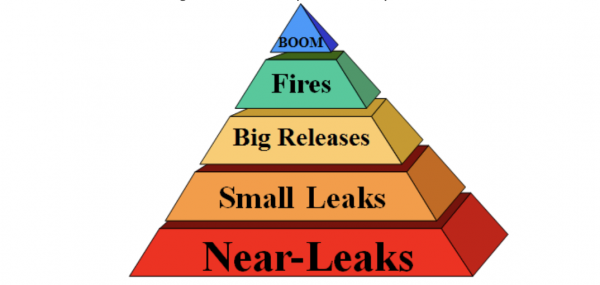

This article is oriented toward identifying and assessing the risk of potentially high consequence, but usually lower likelihood, FEMI issues that could cause a big event at operating sites if sufficient safeguards or barriers are not in place.

In this Reynolds Wrap Up, the author will summarize his key takeaways from a recent robotics event, including interesting applications, challenges that robotic inspection suppliers still face, pros and cons of robotic and UAV inspection, and more.

If I suddenly accepted the position of site manager at your operating site, one of the first things I would do is trot on down to the FEMI group and ask questions to assess what we need to be doing to avoid the potential for big FEMI events.

A summary of some of the important topics that were discussed at the API Fall 2020 Refining and Equipment Standards Meeting that was held via virtual conferencing.

This article presents a methodology for calculating and understanding how many qualified API inspectors you need to staff in order to improve fixed equipment mechanical integrity and reliability at your operating site.

In the author's experience, one of the largest gaps in plants is a lack of understanding of what the entire fixed equipment mechanical integrity group does. This article will shed light on the many roles and responsibilities within these groups.

A summary of some of the important topics that were discussed at the API Spring Refining and Equipment Standards Meeting that was held via virtual conferencing.

There are some significant changes coming in the fifth edition of API RP 751 on Safe Operation of Hydrofluoric Acid Alkylation Units in the section on Mechanical Integrity, Damage Mechanisms and Maintenance Work Practices.

In January of 2019, mechanical integrity professionals from around the world packed into the Grand Ballroom of the Galveston Island Convention Center to attend John Reynolds’ keynote for the API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Summit.

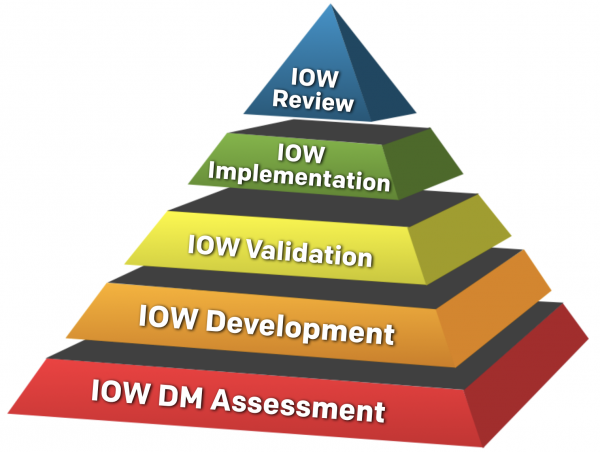

The purpose of this article is to describe some of the pitfalls that operating sites have encountered while trying to implement a program of IOWs in accordance with the guidance in API RP 584, plus how to overcome those pitfalls.

A summary of some of the important topics that were discussed at the API Fall Refining and Equipment Standards Meeting in Atlanta.

Everyone wants fewer leaks and failure of their equipment and piping; but I find very few sites that effectively use one method to make substantial reductions in their piping leaks and failures.

A summary of some of the important topics that were discussed at the Spring Meeting, including the recently-held API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Summit, subcommittee activities, and progress with the API Individual Certification Program.

This article provides a summary of the 2019 API Inspection & MI Summit keynote address, which offers a past, present, and future outlook on fixed equipment mechanical integrity from an industry professional with 50+ years of experience.

The 2019 API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Summit will be kicking off later this month in Galveston, TX. This four-day event will begin with 14 high level training courses offered Monday, January 28th, and then a top notch conference and exhibition running from Tuesday, January 29th through Thursday, January 31st. If you've been then you already know; but if you haven't been, here are the top reasons you need to attend.

A quick summary of some of the important topics that were discussed at the Fall Meeting, including the upcoming API Inspection and Mechanical Integrity Summit, subcommittee activities, and progress with the API Individual Certification Program.

Studying for and passing a test does not necessarily equate to competence as a process or contract inspector for hire. This article explores what it takes to become a capable inspector in this ever-changing industry.

API's biannual meeting pertaining to downstream equipment standards was held in Seattle, Washington this past April. We've summarized some of the discussions and meetings of that you may find interesting, including the 2019 API Inspection and MI...

This article is designed to help the reader better communicate their FEMI Mission, Vision, Core Values and Responsibilities to all stakeholders at their site.

In 2017, a joint-initiative from API and AFPM released a helpful brochure that summarizes all the key API standards that deal with fixed equipment mechanical integrity. It describes the latest edition of 42 API standards addressing FEMI issues, including fabrication, construction, in-service inspection, engineering evaluation, maintenance, and more.

Industry SME John Reynolds provides his bi-annual updates from the API Standards Meeting and discusses developments related to the 2019 API Inspection Summit, SCIMI codes, standards, and recommended practices, and the API Individual Certification...

Although commonly lumped together as a singular acronym, there are important distinctions between Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC). This article defines and distinguishes the role of QA and, in particular, how source inspection factors into that role.

Are your key performance indicators actually driving improvement? Could they be more effective? In this actionable and concise article, John Reynolds is back again to discuss some KPIs you could be using to monitor your progress down the path to FEMI excellence.

35 years ago, an inspection supervisor, some inspectors, and a project engineer could cover an entire refinery. So why are so many more mechanical integrity resources needed today?

Updates and developments related to the 2019 API Inspection Summit, SCIMI code, standard, and recommended practices, and the API Individual Certification Program (ICP).

In this article, the roles and responsibilities of the corrosion and materials SME will be outlined as I see them, fully recognizing that there is probably no one person out there with all the knowledge and skills suggested herein.

The 2017 API Inspection Summit in Galveston was another big success, as evidences by the critique sheets of attendees. Another attendance record was set with 1406 registered attendees, all of whom had choose among nearly 200 different presentations over the three day span.

The Fall API Standards Meeting was incredibly productive and addressed, among other issues, the API Inspection Summit, balloting for the 11th edition of API 510, and improvements to the inspection section of each damage mechanism in API RP 571.

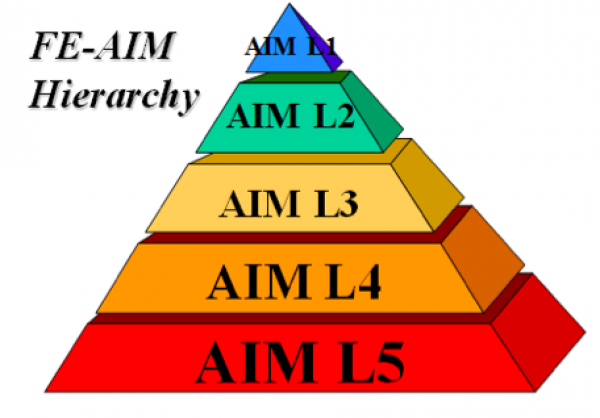

Did you ever wonder where you fit into the entire hierarchy of a fixed equipment asset integrity management (FE-AIM) program? Or who is responsible and accountable for what aspects of FE-AIM at your site? All the way from top management down to those doing the work at the field level? That’s what I will try to address in this article.

I hope by now, everyone is aware that the next API Inspection Summit will be held again at the Galveston Convention Center from January 31– February 2, 2017.

Sometimes with our busyness with the “Daily Grind," we can forget about our most important mission – prevention of a big event caused by an unanticipated fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) failure. Those big events are the ones that...

This brief article contains updates and highlights related to the Subcommittee on Inspection (SCI) at the 2016 API Spring Refining Equipment and Standards Meeting.

We have seen many different inspection recommendation management systems. Most of them struggle to effectively manage all inspection recommendations. However, a few of them are excellent. What makes an effective system?

Updated editions of both API 570 and API RP 580 were recently released by the American Petroleum Institute.

This article provides a summary of the Subcommittee on Inspection (SCI) discussions that occurred at the Fall 2015 API Refining Standards Meeting, including the Inspection Summit Planning Committee and the API ICP Task Group.

Once upon a time in the land of Ooze, there were two processing plants that boiled oil to make fuels and various other valuable petrochemical products. On one side of the river, rests a site called Perfecto Process Plant, while just across the river lies another plant called InZayna Zylum.

Rarely is there a new and unknown cause of a major Fixed Equipment Mechanical Integrity (FEMI) failure in the petrochemical and refining industry. This article briefly summarizes five major fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) failures from the petrochemical and refining industry.

There should be a policy in place and enforced by management at each operating site of not allowing equipment and repair recommendations to become overdue for inspection and handling. Such a practice goes a long way toward increasing the credibility of the inspection efforts at each operating site, as well sending the message that FEMI is just as important as other plant priorities. Of course, in order to get to that point, inspection scheduling, data quality, data analysis, and...

The 2015 API Spring Refining and Equipment Standards Meeting will be held at the Seattle Sheraton during the week of April 13-16, with plenty of interesting meetings for Inspectioneers. You do not need...

Management of change (MOC) for fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) issues is one of the most important of the 101 essential elements in pressure...

The development of advanced NDE techniques/tools is one of the reasons the inspection trade has taken significant steps forward in the last couple decades; and the advancements appear to be accelerating. One of the many ways to keep up with advancing NDE technology is to attend the semi-annual NDE task group meetings at the Spring and Fall API Refining and Equipment Standards Meetings.  In fact, that T/G is planning to document many of the advanced NDE...

Based on my 45+ years of experience working with fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) issues in the refining and petrochemical processing industry, this article summarizes what I believe are the top 10 reasons why pressure vessels and piping systems continue to fail, thus causing significant process safety events (e.g. explosions, fires, toxic releases, environmental damage, etc.).

One of the reasons we continue to have too many fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) events in the refining and process industries is the lack of understanding and appreciation by site management for the hazards posed by the 101 FEMI issues.

One of the most significant advancements to come along in the fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) business in the past two decades is the application of risk-based inspection (RBI) for inspection prioritization, planning, and scheduling. The most important standard for RBI in the petroleum and petrochemical industry is API RP 580.

Based on my 45+ years of experience working with fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) issues in the refining and petrochemical processing industry, this article summarizes what I believe are the top 10 reasons why pressure vessels and piping systems continue to fail, thus causing significant process safety events (e.g. explosions, fires, toxic releases, environmental damage, etc.).

This blog post is the second part of a two part series that assesses the top ten reasons for FEMI failures that cause process safety incidents. The ten reasons I’ve outlined are a result of doing 60+ FEMI audits within refineries and chemical...

Fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) failures are not caused by damage mechanisms; rather, they're caused due to failure to create, implement, & maintain adequate management systems to avoid failures. Nearly all failures that have occurred...

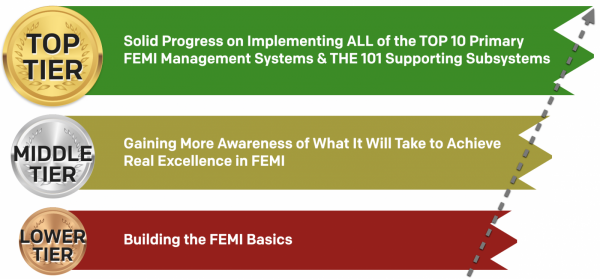

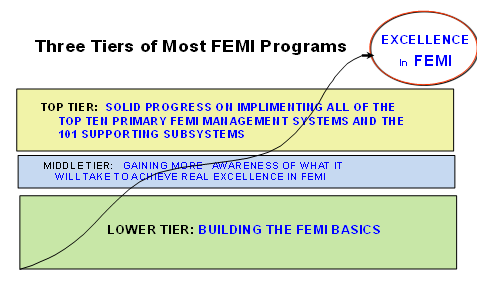

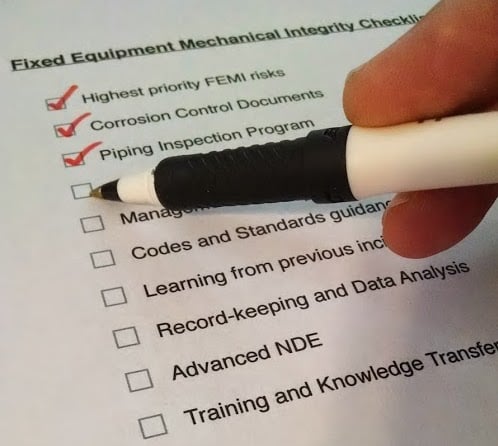

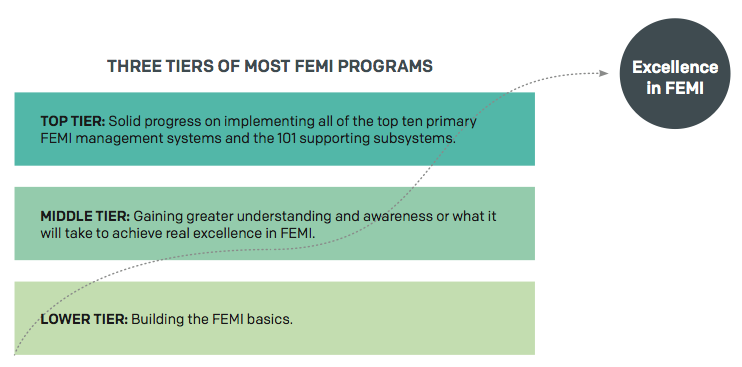

There are typically three tiers to pass through for most fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) programs before they reach excellence in FEMI. In my 45 years in the FEMI business, I have observed FEMI programs in all three tiers (phases).

Three new API standards have been published, and one has been revised and updated to a new edition. The standards are described in this post.

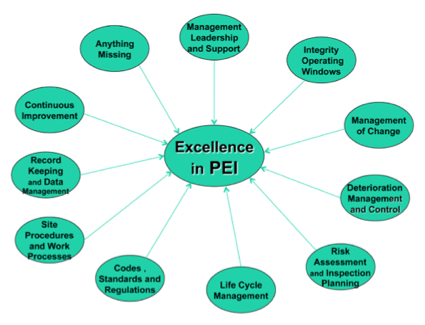

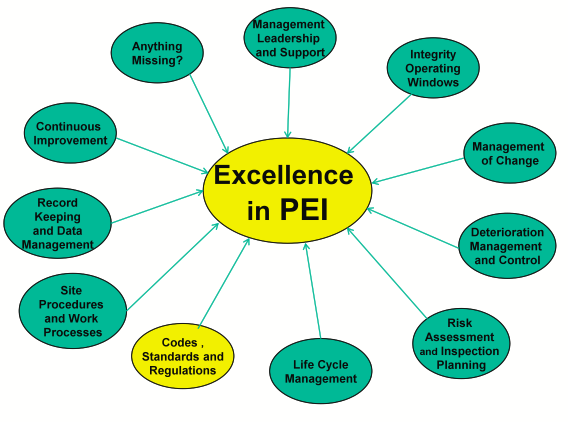

Without an effective organizational strategy for pressure equipment integrity (PEI), many of the 101 essential elements of PEI can "drop between the chairs" because their may be no management systems (MS) in place to make sure that each element of PEI gets properly planned, scheduled, and completed at appropriate intervals by a responsible party.

Today’s blog post is a continuation on the 10 essential Management Systems needed for an effective PEI program that can achieve excellence. My previous posts covered the first six of these, including LCM, Risk Assessment and Inspection, and Deterioration Management and Control, among others.

As I stated in my previous post, there are 10 essential Management Systems (MSs) needed for an effective PEI program that can achieve excellence. These 10 PEI MSs contain all the necessary information that describe what needs to be accomplished, and how to accomplish it, in order to achieve success in PEI.

There are 10 essential Management Systems (MSs) needed for an effective PEI program that can achieve excellence. These 10 PEI MSs contain all the necessary information that describe what needs to be accomplished, and how to accomplish it, in order...

Knowing what needs to be accomplished in order to achieve excellence in pressure equipment integrity (PEI) is one thing, but knowing how to organize it all for success is quite another.

This post concludes the Top 7 reasons why some operating sites "just don’t get it." Reference the previous post for here and here. And for examples of all of the management systems for a sustainable PEI program of excellence, read my article, "The 101 Essential Elements of Pressure Equipment Integrity Management for the Hydrocarbon Process Industry"

These posts came about because, from time to time, I’m asked why some operating sites don’t seem to pay adequate attention to the need to protect and preserve pressure equipment integrity (PEI). Too often a few sites don’t seem to “get it” until they have a major process safety event associated with a failure of pressure equipment. When that happens, they are suddenly on...

From time to time, I’m asked why some operating sites don’t seem to pay adequate attention to the need to protect and preserve pressure equipment integrity (PEI). Too often a few sites don’t seem to "get it" until they have a major process safety event associated with a failure of pressure equipment.

Without doubt management needs to ensure that the appropriate resources (human and budgetary) need to be provided for corrosion control and prevention. The C/M engineer/specialist or other responsible party needs to assure that management is advised annually at the appropriate time what resources will be needed for the next budget cycle.

This week’s post takes up right where last week’s post left off in our discussion on Corrosion Management and Control (CM&C) Management Systems. Here are the last two Corrosion Management and Control Management Systems.

This week’s post takes up right where last week’s post left off in our discussion on Corrosion Management and Control (CM&C) Management Systems.

<p>IÂ have written numerous technical articles addressing how to improve your fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) program. This time I will deviate from the FEMI technologies and methodologies to address a topic that may be equally important to improving your FEMI program – managing your manager(s).</p>

I will emphasize the systems, work processes and procedures for identifying and controlling the rate and types of deterioration in pressure equipment. These are not in any particular order, as they are meant to operate interdependently.

I have written several articles for Inspectioneering Journal to help create successful programs to achieve excellence in pressure equipment integrity and reliability (PEI&R).

One of the reasons we continue to have too many fixed equipment mechanical integrity (FEMI) events in the refining and process industries is the lack of understanding and appreciation by site management for the hazards posed by the 101 FEMI issues.

<p>A new API Individual Certification Program (ICP) will be offered soon to certify inspectors who perform quality assurance (QA) surveillance and inspection activities on new materials and equipment for the energy and chemical (E&C) industry. It is being developed by the API with the assistance of numerous, experienced subject matter experts (SMEs) involved in source inspection activities.</p>

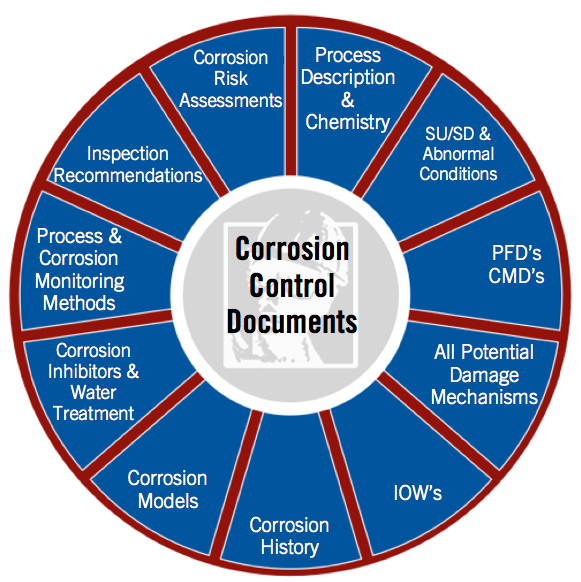

Perhaps the most important work process to achieve success in fixed equipment PEI&R is to create Corrosion Control Documents (CCD’s) for each process unit. In this article, I expand upon that work process in order to guide the interested owner-user in creating CCD’s for their process units.

This is the last out of the ten articles in this series. Clearly, Continuous Improvement (CI) has a major role in achieving excellence in PEI&R. All the advances we’ve made over the years in achieving excellence in PEI&R stems from our continuous improvement programs to apply new and better techniques and methods by learning from what has already occurred.

Clearly, record-keeping and data management have a major role in achieving excellence in pressure equipment integrity and reliability (PEI&R). Everything else we do to achieve excellence in PEI&R stems from keeping high quality and complete PEI&R records, as well as doing all the necessary data analysis.

In the first article entitled How to Put It All Together - Guide to Organizing a Successful PEI Program in the current series of articles that I am writing, I provided an overview of the necessary Management Systems (MS) for a successful program to achieve excellence in pressure equipment integrity and reliability (PEI&R). The eighth article in this series will appear in the November/December issue of the Inspectioneering Journal.

<p>Three new recommended practices (RP) are under way within the API Inspection Subcommittee (SCI) which will add to the list of SCI standards available to owner-users to improve their mechanical integrity (MI) and inspection programs.</p>

In the first article in this series entitled How to Put It All Together - Guide to Organizing a Successful PEI Program, I provided an overview of the necessary Management Systems for a successful program to achieve excellence in pressure equipment...

In the first article in this series entitled How to Put It All Together - Guide to Organizing a Successful PEI Program, (1) I provided an overview of the necessary Management Systems (MS) for a successful program to achieve excellence in pressure...

High Temperature Hydrogen Attack (HTHA) is a long known and still occurring degradation issue for fixed equipment construction materials in the hydrocarbon process industry where hydroprocess plants (hydrogen plus hydrocarbons) are in service....

In the first article in this series entitled How to Put It All Together - Guide to Organizing a Successful PEI Program, (1) I provided an overview of the necessary Management Systems (MS) for a successful program to achieve excellence in pressure equipment integrity (PEI). This is the fifth article in that series. Clearly, Risk Assessment and Inspection Planning have a major role in achieving excellence in Pressure Equipment Integrity and Reliability (PEI&R).

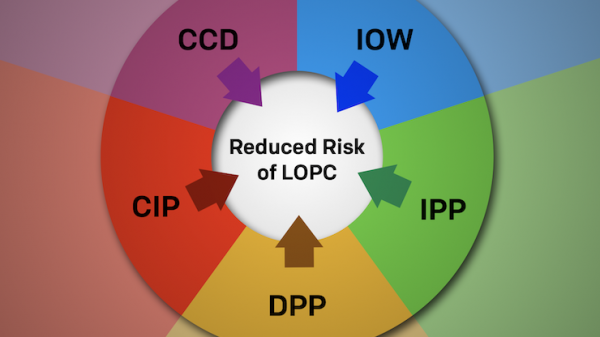

Clearly, corrosion prevention and control has a major role in achieving excellence in Pressure Equipment Integrity and Reliability (PEI&R). But there is a lot more to PEI&R than just corrosion control. This article will show how corrosion control has a central role in PEI&R, but will also show how the management system (MS) for corrosion control must be integrated with 9 other important management systems shown in figure 1 in order to achieve excellence in PEI&R.

This article in the series will focus on two more of the necessary MSs for achieving excellence in PEI: Integrity Operating Windows (IOWs) and Management of Change (MOC).

Like all of the other 10 MSs in our filing cabinet, this MS on Management Leadership and Support of PEI (shown in Figure 2 below) is vital to success and linked inextricably to all the other PEI MSs.

Knowing what needs to be accomplished in order to achieve excellence in pressure equipment integrity (PEI) is one thing, but knowing how to organize it all for success is quite another.

The ASME Post Construction Committee (PCC) has embarked upon a noble activity to produce a guide to using codes, standards, recommended practices, specifications and guidelines that can be used by manufacturers, owners, users, regulators, engineers and all other stakeholders in the total life cycle management (LCM) of pressure equipment. As most of know, there is a very wide array of such documents available and to the best of my knowledge there is no comprehensive guide to how all these documents can be tied together in the cradle to grave management of pressure equipment, from concept to decommissioning.

After pressure equipment (aka fixed or static equipment) is designed, fabricated, and constructed to new construction codes and standards (C/S), it is placed in-service, at which time the API In-service Inspection (ISI) C/S and ASME Post-Construction C/S begin to govern. Within the API Standards Organization, the Subcommittee on Inspection (SCI) produces and maintains most of the ISI standards that govern in the refining and chemical process industry. Also within the API, the Corrosion and Materials Subcommittee (CMSC) produced many recommended practices that are referenced in the ISI C/S. Within the ASME, the Post Construction Committee (PCC) produces and maintains most of the post construction (means the same as ISI) standards that govern equipment after it has been placed in-service.

This paper covers most of the common (and some not so common) types of NDE methods for heat exchanger (HX) tubular in-service inspections. In addition to noting some of the various advantages and limitations with these methods, the paper covers heat exchanger tubular inspection planning, data analysis needs, a consequence rating method for scheduling inspection and bundle renewals, tubular cleaning methods and tubular inspection technician qualifications.

OSHA’s National Emphasis Program (NEP) (1) is now well underway, with 17 of 81 targeted refineries having been reviewed so far (2). OSHA launched the NEP in 2007 after the deadly incident at BP Texas City. As of March this year, OSHA claims to have uncovered 146 violations so far and recommended nearly $1 million in fines.

<p>In May of this year, a workshop was presented at the annual NPRA Reliability and Maintenance Conference at the George R. Brown CC in Houston. This article is a reader’s digest summary of what was presented at that workshop by the four panelists.</p>

From time to time, I'm asked why some operating sites don't seem to pay adequate attention to the need to protect and preserve pressure equipment integrity (PEI). Too often a few sites don't seem to "get it" until they have a major process safety event associated with a failure of pressure equipment. And unfortunately when that happens, they are suddenly on board with PEI needs and don't seem to be able to apply their available resources fast enough. Fortunately, I see less and less of this type behavior as time passes and the word spreads throughout the industry about PEI catastrophes and how to avoid them.

A myriad of issues need to be considered before welding to or repairing weld overlayed or clad equipment. (By clad we mean roll-bonded or explosion bonded, i.e. basically 100% metallurgically bonded, and not a loose or seam-welded liner, e.g., not strip lining.)

In the welded condition many stainless steels are susceptible to rapid intergranular corrosion or stress corrosion cracking. This is because the heat from welding sensitizes the base metal heat affected zone (HAZ) and the weld.

When we talk about welding QA/QC we typically focus on the technical requirements and what QA/QC is needed to assure that the technical requirements are met. Examples include the preheat, interpass, and PWHT temperatures and how to assure that the...

<p>In previous parts of this series, I have covered many corrosion and degradation issues, some environmental cracking diseases, metallurgical degradation mechanisms, issues associated with welding and some external corrosion problems. In part 14, I’m going to cover one of the most insidious “diseases” associated with process equipment that can and does cause catastrophic pressure equipment failures: brittle fracture.</p>

As noted in the discussion on delayed cracking, when the steel contains hydrogen as a result of service exposure (or corrosion, or high temperature - high pressure hydrogen processing) then a hydrogen bake out may be needed to avoid cracking problems during or after welding.

Among other things, a welding QA/QC program needs to ensure that only qualified welders, utilizing qualified procedures are allowed to weld on any pressurized equipment, including storage tanks and piping.

After a pressure equipment or piping failure, it’s not uncommon to find out during the failure analysis part of the investigation that the failure initiated at a welding flaw of some sort.

The API Subcommittee on Inspection, Task Group (T/G) on Inspector Certification is starting to roll out a new program for Inspector Certification Endorsements (ICEP). This program will cover each of several new API Recommended Practices and cover the following subject matters...

Strain-aging problems are another form of metallurgical degradation and thankfully are not very common and becoming less so; but since strain-aging does still occasionally occur, it still makes the list of one of the “99 diseases of pressure equipment”.

Another form of metallurgical degradation at higher temperatures is called sigma phase embrittlement. As the name implies, a metallurgical phase change occurs in some stainless steels when they are heated above about 1000F (540C).

Temper embrittlement is another form of metallurgical degradation resulting from exposure of susceptible low alloy steels to higher temperature ranges, usually in service, but can occur to some extent even during heat treatment. And, once again, if significant temper embrittlement has occurred, the equipment may be susceptible to catastrophic brittle fracture.

Titanium (Ti) hydriding is another somewhat unusual metallurgical degradation phenomena that can result in brittle fracture. Unlike many other steel embrittlement phenomena, this one most often occurs in thin wall Ti tubes that have been selected for their superior corrosion resistance of overhead condensers.

<p>Spheroidization is a rather technical term that describes a metallurgical aging phenomena that results in loss of mechanical and creep strength. It occurs when carbon and low alloy steels are exposed to temperatures in the range of 850F - 1400F (440C - 760C) where carbide phases (the strengthening element of steels) become unstable and begin to agglomerate, which then results in the loss of strength.</p>

<p>Metals will slowly deform under stress and higher temperatures by the mechanism known as creep. The amount of creep deformation that will be experienced is highly dependent upon the level of stress, level of temperature and material properties. It is vital that any component operating in the creep range have Integrity Operating Windows (IOW’s) established where upon operators are required to make adjustments if certain temperatures are reached.</p>

Cooling water (CW) corrosion may be the oldest form of corrosion in the petrochemical industry, yet the industry still struggles with it for two primary reasons.

Boiler feed water (BFW) corrosion is mostly the result of dissolved oxygen in the feed water, but is also related to the quality of the BFW and the quality of the treatment system.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) corrosion is most typically found in boiler condensate return systems that are not adequately treated with corrosion inhibitors (typically amines). Dissolved CO2 in condensate forms carbonic acid (H2CO3) which corrodes steels and low alloys to form a iron carbonate scale.

MIC is caused by biological growth, i.e. organic slime (typically bacteria, algae, and fungi) in water under low flow or stagnant conditions. The industry experiences it in cooling water systems, piping, vessels and storage tank bottoms where the...

<p>Most all flue gases produced by the combustion of fuels contain contaminants that can condense into acid droplets. The amount of contaminants will determine the concentration of the acid droplets.</p>

One of the more important uses of the 99 Diseases of Hydrocarbon Process Equipment is to determine how to safely operate process pressure equipment. Such a work process thereby minimizes the impact of any potential degradation mechanisms (the 99 Diseases), by establishing the appropriate boundaries for long and short-term safe process operation. Such boundaries are called Integrity Operating Windows (IOW's).

<p>Corrosion fatigue is closely related to mechanical and vibration fatigue cracking, except that it is initiated and accelerated by a corrosion mechanism, especially one that gives rise to pitting, from which cracks often initiate. But that corrosion mechanism need not be very severe in order to give rise to corrosion fatigue. Probably the best known case of corrosion fatigue, in a lightly corrosive environment, stems from deaerators in boiler systems.</p>

Hydrogen stress cracking occurs when corrosion from acids like wet hydrogen sulfide or hydrofluoric acid (HF) cause atomic hydrogen to penetrate hardened or higher strength steels and cause stress cracking.

Polythionic Acid Stress Corrosion Cracking (PASCC) is an affliction of many refineries processing sulfur containing feedstocks, and since that is the norm these days, most refiners reduce their susceptibility to PASCC by selecting resistant alloys orby neutralizing exposed surfaces during shutdowns.

<p>HTHA falls into multiple categories of corrosion mechanisms, including environmentally assisted cracking, hydrogen assisted cracking, and high temperature degradation. Sometimes HTHA is confused with low temperature hydrogen cracking mechanisms that result from hydrogen being driven into steels by aqueous corrosion reactions.</p>

Amine cracking is a form of stress corrosion cracking, which is related to alkaline and carbonate stress corrosion cracking. Amine cracking is often intertwined with wet H2S and carbonate cracking, as amines, carbonates and wet sulfides often exist together in amine treating systems.

Unfortunately there is a recurring theme of pressure equipment integrity incidents in the hydrocarbon process industry which has been identified by the API and that is leaks and fires caused by the inadvertent substitution of materials of construction in piping systems - the so called positive materials identification (PMI) incidents.

Corrosion in the refining industry from HFA is not as widespread a problem as it is with HCl because it is only associated with HF Alkylation Units, which are usually fairly carefully controlled in order to avoid potential for a toxic HFA cloud after a leak.

<p>Unlike NAC where we’re still on a learning curve, the knowledge of corrosion by sulfuric acid has not changed much in the last quarter century, and there are many good references for it included in API RP 571.</p>

Corrosion from HCl is a significant problem in many refining and chemical process units, and often the materials solution to HCl corrosion is rather expensive, since the lower cost, more available alloys are usually not resistant to most concentrations of HCl.

Problems with naphthenic acid corrosion (NAC) are nearly as old as the refining industry. The first paper on the topic that I knew about was written by one of my early industry supervisors over 40 years ago.

<p>Corrosion from phosphoric acid is another “old knowledge” corrosion issue that effects only a few processes in the chemical and hydrocarbon process industry.</p>

High temperature sulfidation is probably the most common high temperature corrosion nemesis in the refining industry, since there are very few “sweet” refineries still in operation. Sulfidation corrosion typically is of concern in sour oil services starting at temperatures in the 500F (260C) range.

<p>Though oxidation and sulfidation are quite prevalent high temperature corrosion mechanisms in many of our process units, we now come to a few that are not very common, but still deserve some attention to make sure they don’t lead to unexpected failures.</p>

<p>Metal dusting is simply a severe form or extension of carburization in which the extensive carbides that form as a result of carburization lead to grains of metal falling out of the tube or piping and being swept away by the process stream.</p>

High temperature oxidation is not a real common type of failure in our industry, but it can and does happen when temperatures exceed design maximums. All metals oxidize, even at room temperature, and in many cases that slow oxidation process actually protects the metal from rapid oxidation.

Decarburization is the antithesis of carburization and rarely results in equipment failure. However, surface decarburization is often a sign that something more serious is going on, ie high temperature hydrogen attack (HTHA), which is well covered in API RP 941, Steels for Hydrogen Service at Elevated Temperatures and Pressures in Petroleum Refineries and Petrochemical Plants.

<p>CUI may be the most well known and widespread corrosion phenomena in our industry. It’s also one of the most difficult to prevent because by and large no matter what precautions we take, water eventually gets into the insulation and begins to do it’s dirty work, sometimes sight unseen until process leakage occurs. And it’s not isolated to just insulation. Corrosion under fire-proofing (CUF) is also prevalent in our industry and requires the same type of inspection planning, design prevention, and mitigation that is required for CUI.</p>

<p>For purposes of this article, external (atmospheric) corrosion is what afflicts process equipment and structural members that are not insulated and exposed to moisture associated with atmospheric conditions, ie rain, condensation from humidity, marine spray, cooling tower mists, industrial pollutants, etc.</p>

Soil corrosion (underground corrosion) is another one of those extensively researched and documented types of corrosion, since so many pipes and pipelines are buried and nearly all storage tanks rest on the soil. An entire industry/ technology is associated with preventing soil corrosion (cathodic protection).

Chloride cracking of austenitic stainless steels (300 series SS) is an off-shoot of CUI, and there’s nothing really magical about it. If you have insulated solid stainless steel equipment operating in the CUI temperature range you are likely to eventually experience External Chloride Stress Corrosion Cracking (ECSCC).

ASME has an active Post Construction Committee (PCC) for generating standards for in-service inspection. As such, the ASME is no longer just a "new construction" standardization organization. The Subcommittee on Repair and Testing now has 23 chapters in preparation on various methods of conducting repairs (temporary and permanent) on pressure equipment, tanks and piping.

<p>Cracks along the toe of a weld are not uncommon during fabrication, and can occur for a wide variety of reasons involving the metallurgy and process control of the the same issues covered above on repair welds can apply to repair welds on castings; especially if you are unaware that the foundry or fabricator is trying to salvage a defective casting by covering up porosity and shrinkage cracking with a big glob of weld metal.</p>

Casting defects are an age old problem for our industry that seems to be getting worse as foundries in the older industrialized world shutdown for economic reasons.

Inadequate PWHT is one of our pressure equipment nemeses. We normally specify PWHT for a variety of pressure equipment integrity reasons including when we need to lower residual stresses, increase resistance to cracking or soften weld hardness. All for the purpose of prolonging the service life of our equipment and preventing unexpected failures. But this issue is clearly where those old sayings of "Buyer beware" and "You don't get what you expect, you get what you inspect" apply quite often.

Speaking of stress raisers, they are another insidious type of flaw that can and do lead to equipment failures. Stress raisers (aka stress intensification sites) can be mechanical or metallurgical notches. Undercutting, physical weld flaws, mismatched thicknesses, and sharp geometric intersections can all become stress raisers. But so too can so-called "metallurgical notches" like one finds at the edge of a weld where the cast structure of the weld pool meets the wrought structure of the heat-affected zone. Equipment in many static services without significant cyclic stresses can tolerate the presence of some stress raisers because of hefty code design margins. But equipment in services with significant fatigue stresses (thermal and mechanical) are especially vulnerable to such notches and deserve special QA/QC attention during design, specification, fabrication, and repairs.

Repair welds can be another undetected and insidious "fabrication defect" that eventually results in equipment failure. Any experienced metallurgist that has completed numerous failure analyses over the years will tell you that periodically they see failures that initiated at the site of a repair weld. Sometimes those repair welds are field repairs, but not infrequently they occurred during original fabrication and were unknown to the purchaser. Typically our standards and specifications do not cover repairs completed by the fabricator, so they believe they are free to do whatever they want to repair a manufacturing or fabrication defect, then grind it flush, finish the fabrication and ship the product.

There are a variety of forms of wet H2S cracking. In this short article I will focus on two of the most common forms: hydrogen induced cracking and stress-oriented hydrogen induced cracking (HIC/ SOHIC). HIC is often fairly innocuous (but not always), while SOHIC is a type of cracking that can easily lead to failure and needs to be mitigated. HIC is a form of tiny blistering damage that is mostly parallel to the surface and to the direction of hoop stress, hence is usually not damaging until it is extensive and affects material properties or gives rise to step-wise cracking that propagates into a weld or begins to go step-wise through the wall.

Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) is an insidious form of degradation that can strike during equipment fabrication, cleaning, repairs or while in-service. It stems from the infusion of atomic hydrogen into some higher strength steels that then leads to embrittlement, cracking or catastrophic brittle fracture.

Liquid Metal Cracking (LMC) (aka "liquid metal embrittlement") is another insidious form of cracking that strikes when you least expect it. It most commonly afflicts austenitic stainless steels, but can afflict other copper, nickel and aluminum alloys. LMC occurs when molten metals come in contact with susceptible materials. One of the more common such occurrences is during a fire when molten zinc from galvanized steel parts or inorganic zinc coatings drips down on SS equipment.

Ammonia stress corrosion cracking (SCC) has been around a long time. Most everyone has experienced it from time to time. It's not uncommon in brass tubes in cooling water service that is contaminated with ammonia due to biological growths or other contamination. Sometimes ammonia is added intentionally to process streams as a neutralizer by folks who do not know what it might do to brass tubes. Brass condenser tubes will fail brittlely when bent after they have significant ammonia stress corrosion cracking present. Eddy current inspection of brass tubulars is effective at finding ammonia cracking. Cupro-nickel alloys are usually not susceptible, and if necessary you can upgrade to austenitic stainless steels (which has it's own set of problems).

Carbonate cracking (CC) of carbon steel has seen an increase recently in frequency and severity in some refinery cat crackers, especially in fractionator and gas processing overheads. Some gas scrubbing units are also susceptible. CC is a form of alkaline stress corrosion cracking that often occurs more aggressively at higher pH and higher concentrations of carbonate solutions.

Chloride stress corrosion cracking (SCC) is about as well known as any SCC mechanism can be, so I won't dwell much on it here, but want to mention it for the sake of completeness and hopefully mention something that is not as commonly known about it. Chloride SCC is clearly the bane of austenitic stainless steels and one of the main reasons they are not the "miraclecure" for many corrosion problems.

The API Inspection Subcommittee has issued the second edition of their inspection benchmarking survey. We are encouraging as many sites, worldwide, to participate as possible, so that we have the most amount of data available for analysis and conclusions.

Cavitation is the sudden formation and immediate collapse of vapor or air bubbles in a liquid stream when system pressure falls below the vapor pressure of the liquid. The sudden collapse of these tiny bubbles generates enormous, though tiny forces that mechanically damage (erode) metal (often on pump impellers or just downstream of let down valves).

Few of us have not experienced or heard about vibration fatigue (cracking) failures, especially around pumps and compressors. Typically small branch connections, equalizer lines, vents and drains are susceptible, especially if they are screwed connections. Such failures have often led to safety and reliability events because of the sudden release of flammable hydrocarbons.

Thermal shock is another one of those pressure equipment afflictions where communication with operating groups is a vital factor in prevention. Thermal shock failures usually involve sudden quenching of high temperature equipment and furnace tubes with a relatively cooler liquid or saturated steam containing some liquid, but not always.

Graphitization is not something that operators can do much about, and thankfully it is not very common. We as engineers and inspectors have to know about this one and prevent it or detect it. It occurs when the microstructure of some carbon and low alloy steels breaks down after long exposure to elevated temperatures, like in FCCU's.

<p>This is the name given to a form of embrittlement that occurs in 400 series of stainless steels, duplex SS's and less commonly in some 300 series stainless steels containing a metallurgical phase called ferrite. The embrittlement occurs from 600 F to 1000 F, but most readily at a temperature of 885 F, hence the name.</p>

Next year, the API Inspector Recertification Program (ICP) will be recertifying inspectors who have held their API certifications for more than 6 years. Things have changed this time though, and inspectors will be required to pass a short exam covering material that has changed in the past 6 years.

A new recommended practice from the API is in the final stages of preparation before publications. It is API RP 577 on Welding Inspection and Metallurgy.

Welcome to a new series of articles about the ninety-nine leading types of degradation, flaws and failure that can and do happen to pressure equipment in the hydrocarbon process industry.

<p>I already mentioned this common affliction in the introduction. Caustic cracking was long called caustic embrittlement, but since no embrittlement actually occurs that name is fading away.</p>

Now you say, he's got to be putting me on. What is green rot? I didn't invent it. I first read about it in one of the early texts on corrosion engineering by Ughlig or Fontana, the venerable corrosion professors at MIT & Ohio State. But when I experienced it, it became very real, even though I've only seen it once in my 35-year career.

This failure mechanism is unfortunately all too common in our industry. It's also known as stress rupture, and it is usually entirely preventable by proper maintenance and operating procedures. It occurs when equipment, piping or furnace tubes that are designed to operate safely and reliably in one temperature range are suddenly (and sometimes not so suddenly) exposed to higher temperatures.

An effort is currently underway to create a new code for in-service inspection and maintenance of pressure equipment in the hydrocarbon process industry. The API Committee on Refinery Equipment (CRE) and the ASME Board on Pressure Technology Codes & Standards (BPTCS) have agreed to explore the idea by putting together a joint task group that would report to both organizations. That group will be meeting soon to put together a set of committee operating procedures and the scope/objective of the document for approval by the API CRE & ASME BPTCS. Once the charter/scope and operating procedures are approved by both societies, a committee will be assembled to accomplish the task.

In May 2002, after 6 years of preparation, the API published the first edition of API 580 Risk-based Inspection. The document is now an ANSI/API Standard, which was balloted and approved using the ANSI consensus process for creating American National Standards. As such it becomes a "recognized and generally accepted good engineering practice", for use by all companies in the oil and chemical industry.

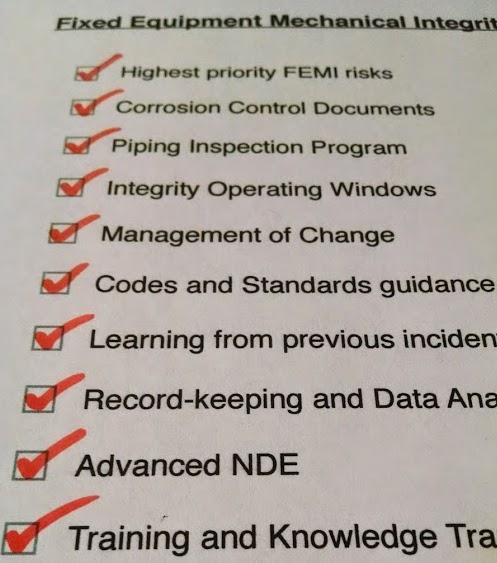

Part 5 of this article continues to outline the 101 essential elements that need to be in place, and functioning well, to effectively and efficiently, preserve and protect the reliability and integrity of pressure equipment (vessels, exchangers, furnaces, boilers, piping, tanks, relief systems) in the refining, gas processing and petrochemical industry.

Part 4 of this article continues to outline the 101 essential elements that need to be in place, and functioning well, to effectively and efficiently, preserve and protect the reliability and integrity of pressure equipment (vessels, exchangers,...

This article continues to outline the 101 essential elements that need to be in place, and functioning well, to effectively and efficiently, preserve and protect the reliability and integrity of pressure equipment (vessels, exchangers, furnaces,...

This paper outlines the 101 essential elements that need to be in place, and functioning well, to effectively and efficiently, preserve and protect the reliability and integrity of pressure equipment (vessels, exchangers, furnaces, boilers, piping...

This is the first of a series of articles that outlines the 101 essential elements that need to be in place, and functioning well, to preserve and protect the reliability and integrity of pressure equipment (vessels, exchangers, furnaces, boilers, piping, tanks, relief systems) in the refining and petrochemical industry.

Two API projects are co-sponsoring an effort to develop a risk based inspection (RBI) method for atmospheric storage tanks (AST). One of the projects is the long standing RBI project that is developing RBI methods for all types of pressure equipment; and the other is the more recently formed group that is focused on developing risk assessment methods for oil and gasoline terminals and other storage tank facilities. This article covers the preliminary model that has been proposed for both projects by the joint contractor for both projects, DNV. As such, this model is a draft and still undergoing review and revision by the two API project groups.

This is part three of a three part article for the IJ describing some of the advanced on-stream inspection (OSI) methods available for use in inspection of pressure equipment in the petroleum and petrochemical industry. These methods can be used, under the right circumstances, to supplement or in lieu of invasive and turnaround inspections, usually at much lower cost. Cost savings associated with using OSI techniques in lieu of internal inspection may include lower total inspection costs, lower turnaround costs, avoiding lost production opportunities, and avoiding vessel cleaning and decontamination costs. On-stream inspection also avoids the safety hazards associated with confined space entry of vessels. However, to achieve these savings and benefits, and still maintain high levels of pressure equipment integrity, the owner-user must understand the technologies in order to intelligently select, apply and interpret the results of these nondestructive evaluation (NDE) methods.

This is part two of a three part article describing some of the advanced on-stream inspection methods available for use in inspection of pressure equipment in the petroleum and petrochemical industry. These methods can be used, under the right...

This three-part article describes some of the advanced on-stream inspection methods available for use in inspection of pressure equipment in the petroleum and petrochemical industry. These methods can be used, under the right circumstances, to...

Some Middle Eastern and European operators are now using AE successfully to screen tanks for internal inspection by listening for active tank bottom corrosion, and then grading the tank as high, medium or low need for internal inspection.

In Part 1 of this article, in the last edition of the IJ, I introduced the work process that we use to assess the effectiveness of our pressure equipment integrity (PEI) management. It involves a self-assessment workbook filled out by site personnel, which is in turn reviewed and validated by a team of company auditors from outside the site. I also introduced the seven major categories of assessment that we conduct.

In this first part of a two-part article, I will outline a process that our company uses to review and measure the effectiveness of our pressure equipment integrity management process. Then in Part 2, next issue, I will "fill in the blanks" on some specific issues that we measure.

This is the fourth in a series of articles on piping inspection that I'm writing for the Journal. One of the previous ones dealt with improving thickness data taking accuracy with digital ultrasonic methods. This article is a "sister article" that deals with improving the accuracy of profile radiographic inspection techniques, also called isotope radiography, wall shots, or tangential radiographic inspection.

In the Jan/Feb issue of the IJ, I mentioned how important the Management of Change (MOC) process is when it comes to maintaining safe, leak-free piping systems; stating that we in the inspection business cannot do it alone; that is, we taint the integrity of piping systems without a lot of help from operating personnel and operations support engineers.

This is the second in a series of articles on piping inspection. In the last article, I enumerated four inspection issues that I believe contribute to inadequate piping mechanical integrity in the hydrocarbon process industry.

It's probably more important to those of us who don't have a brain tumor. Unfortunately, it's precisely because piping inspection is not neurosurgery that it's often done poorly, which can lead to significant impacts on process unit reliability, or worse, a catastrophic event, where people can get hurt.

Three levels of risk based inspection have been developed by the API sponsor group. Level 1: Qualitative RBI which utilizes a step-by-step workbook to rank entire process units or process systems into a 5 x 5 risk matrix...

In the January 1995 issue, I introduced the concept of Risk-Based Inspection (RBI) being developed by an API (American Petroleum Institute) project. This article is an update and status report on that project, which now has 20 sponsor companies, and more joining each quarter.

Are your jurisdictional boiler and/or pressure vessel rules and regulations too stringent, too costly, too bureaucratic, without adding real safety value commensurate with the time and resources necessary for compliance? Are you having to hire third party inspectors to perform boiler and/or pressure vessel inspections, when you have fully qualified, competent inspection resources on staff? Are you having to shut down safe, reliable boilers and/or pressure vessels annually (or bi-annually) just to comply with outdated boiler and/or pressure vessel (B&PV) inspection requirements? If the answer to any of these questions is "yes" for your company, read on: you may be interested to know that times are changing.

There are a lot of vital roles in the success of any refinery or petrochemical process plant. But none are more important to success than that filled by the pressure equipment inspector (PEI). Years back, we recognized that world class pressure equipment integrity and reliability was critical to our success. Engineering management knew that if we didn't have that, we could not succeed in our business strategy, no matter how good we were at all other necessary functions.

In our inspection organizations, we have identified a number of critical success factors (CSF's) which are vitally important if we are to achieve the level of pressure equipment reliability and integrity to which we aspire. One of our CSF's is the level of service provided to our refineries and chemical plant sites by our Nondestructive Examination Technical Direction Team.

In August of 1993, the hydrocarbon process industry once again experienced a catastrophic loss when a major coker unit fire occurred in Louisiana. The cause of that incident was not unlike many others that have occurred over the years throughout the industry: inadvertent substitution of construction materials.

Late in 1994, the API surveyed their committee on refining equipment members in order to provide benchmarking information on the extent of Pressure Equipment Inspection (PEI) activities and programs underway at member companies.

<p>As chairman of the API Inspection Subcommittee, one of the questions I often receive involves the difference between the API Pressure Vessel Inspection Code (API-510) and the National Board Inspection Code (NBIC).</p>

Many promising advances are being made in inspection technologies, today. Some are going to provide opportunities for companies to maintain and increase equipment mechanical integrity, quite possibly at lower costs.