| This article is part 1 of a 3-part series. |

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 |

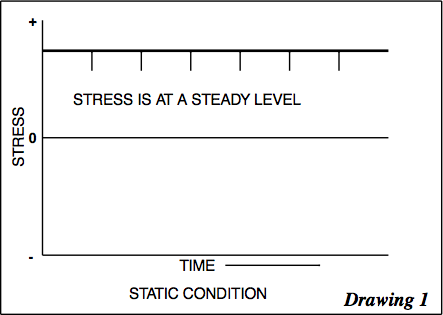

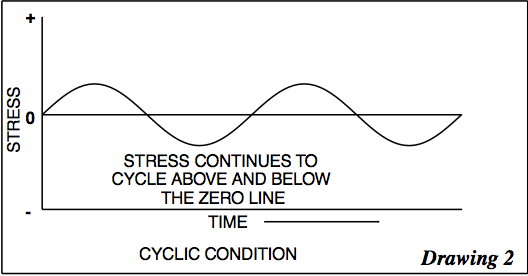

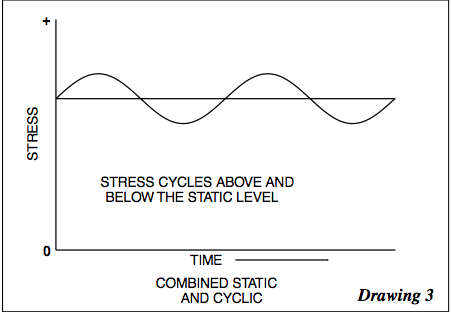

A continually frustrating phenomenon to many of us is the situation where a tight bolt will function satisfactorily, but in the same situation, a loose bolt will fail. This performance behavior is based on two fundamental types of loading that a bolt may encounter. One is called “static” or steady state loading, and the other is called “cyclic” or a continuously changing load. This changing load usually follows a repeated pattern, i.e., so far plus and so far minus from a given mean level. Both of these conditions, plus a combination of both, are shown graphically in Drawings 1, 2 and 3.

The cyclic strength range is, at best, onehalf, and it has been known to be as low as one-tenth.

Bolts involved in process equipment are seldom loaded in a pure static or pure cyclic condition. The pretension or torque up of a bolt is a static component. Loading, such as that from pressure pulsations, is a cyclic component.

The most immediate illustration of this combination condition is the flat faced flange connection such as used to attach a horizontal compressor cylinder to the crankcase. If the bolts are torqued properly (static load), the cyclic load component on the bolts from the reciprocating compressor operation will be small. The bolts will be in a so-called “protected condition”. If the torque is too low, and the flange faces are allowed to separate, the bolts lose that protection and see the full cyclic component - and usually fail.

In the next issue, we will deal with the physical basis for this behavior.

Comments and Discussion

There are no comments yet.

Add a Comment

Please log in or register to participate in comments and discussions.